Thursday, December 27, 2007

Garrison Keillor's Writers Almanac: "What My Father Believed"

http://writersalmanac.publicradio.org/programs/2007/12/24/#friday

This poem talks about my father's faith, how he learned about God in Poland as a child, and how his faith sustained him in the concentration camps in Nazi Germany.

Friday, December 21, 2007

Merry Christmas and Happy 2008 to All our Friends and Family!

.

I want to mention first that Linda’s Uncle Charlie died in August. Some of you who’ve read my blogs about him know he had pancreatic cancer that grew increasingly bad over the summer. Linda and I drove down to Florida a number of times to be with him and help him as his condition got worse. He died quietly in his sleep on August 24th. We’ll miss him.

Linda’s big news is that she’s decided to retire as of July 1, 2008. She’s been envying how laidback I’ve been since I retired, and she finally turned in her letter. I’ve noticed already that she seems more laidback than before. In fact, our cat Samantha has been spending more time sleeping on her stomach than on mine. I may have to get my own cat if Linda gets any more laidback.

Linda’s plans for our retirement? We hope to do more traveling. We’ve started talking about a big, long, two or three week cruise through the Panama Canal and up the boot of Baja, California, and out across the Pacific, maybe to Hawaii or maybe further to Tahiti or Thailand or Taiwan. Or maybe we’ll just stay here in the states and do a Casino Crawl from Las Vegas to Henderson to Reno and Winnemucca, Nevada.

By the way, she wanted me to tell you all that the pecan picking this year has been superb. Bigger nuts and more of them! She thinks it may have something to do with the presidential primaries that are coming up.

Lillian continues to enjoy teaching in Danville. This is her fourth year at George Washington High, and she’s recently been tenured. Like her mom, Lillian is interested in going beyond the classroom. She’s been commuting to Lynchburg College two or three nights a week this year, where she’s been working on her Master’s in Educational Leadership. This coming May she’ll be getting that Master’s. By the way, this last summer, she served as principal at her high school! She expelled five students!

I’ve been focusing on my writing. I published Lightning and Ashes and Third Winter of War. The latter was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry. Right now, I’m working on a novel about a German soldier in Russia during WWII. Joyce Carol Oates published the first chapter in her journal Ontario Review. I’m also blogging as fast as I can and doing presentations about my parents all over the place, and if you read this before December 28 you can hear Garrison Keillor reading my poem “What My Father Believed” on NPR’s Writer’s Almanac.

Love from us to you,

Linda and John

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

Pecan Picking Time in Georgia--Guest Starring Linda Calendrillo!

Friday, November 16, 2007

The Skies Over America by Matt Flumerfelt

THE SKIES OVER AMERICA

The skies over America

are vibrant as a Pollock painting

and dissonant as a Schoenberg

symphony. They’re the canvas

on which we scrawl the graffiti

of our lives.

.

Ours is a garden where

every flower may flourish,

bitter nightshade and evening

primrose, a Mendelian greenhouse

where hybrids are the rule

and whore lies down with priest.

.

We’re enamored of the camera.

If we could, we’d like to film

the destruction of the world,

even though no one would be left

to watch it explode a second time

except a few seagulls.

.

America was born to immigrant

parents in a sharecropper’s shack.

Three acres and a mule were its

only possessions. It was suckled

on hard work, cheap whiskey,

tobacco, cornbread and collard greens,

and the promise of eternal life.

.

The skies over America

are crumbling. They’re responding

well to therapy. They need

more antioxidants, plastic surgery,

yoga lessons. They’re weeping.

The skies over America are

closed for remodeling.

Matt's poem "The Skies Over America" is from his new book The Art of Dreaming.

It's available for $10, plus $2 for shipping.

You can order The Art of Dreaming from him at

29 loganberryCircle

Valdosta Ga 31602

.

Or you can email Matt at mattflumerfelt@bellsouth.net

Thursday, November 01, 2007

Valdosta Halloween--2007

The pirate kid was proud of his costume even though he didn't have a hat or wig. He left them in the car his mom was using to drive him from one house to another. He said, "It's just too hot for a wig. That's why I'm not wearing one!" We gave him a quarter.

This pirate boy stopped by at about 7 pm.

After that, it was quiet.

At about 730, I went outside and stood on the front porch for a while to see if there was anyone coming. There was no moon yet, and all the houses on both sides of the street were dark. A car drove past going west toward the Walmart near I-75.

I looked across the street at the house where these 3 young girls live. It's a big old Victorian just like ours. Every year we've been in Valdosta, the girls have made it over--even when the youngest was 1. She wore a white and gold princess costume that year, and had her big white cat with her. The cat didn't wear a costume.

This year they didn't make it.

Their house was dark.

Thursday, October 11, 2007

Simple Polish Soup

I like Tania. She's a good person and a good poet, so I said I would.

Here's the recipe I sent her:

Hi, Tania,

I'm no good at cooking, so I can't vouch for anything I say about recipes or food or putting stuff on the table. I commuted for 8 years, was away from my wife for 2-3-4 days at a time, made my own food and everyday I ate the same thing, a micro waved veggie burger and a can of Progresso minestrone soup.

Having said that, let me say that the following is a real recipe.

Here it goes:

When my mother was in her late 70s, she couldn't cook for herself any more. Her heart and her back had both given out, and she couldn't stand for more than a minute or two. When you can't stand, you can't cook.

She started having her meals brought in by a charitable organization in Sun City, Arizona, where she lived after my dad died. This food was pretty miserable: Salisbury Steaks, tuna salad sandwiches, little cups of salad, vanilla cup cakes--stuff like that, five days a week. They would bring a white bag of this everyday around noon, and it was expected to last her through lunch and dinner. On the weekends she was on her own. She would have a friend bring her some chicken from KFC or a piece of cooked ham from the deli section at the Safeway Supermarket down the street. She would microwave this food Saturday and Sunday. Monday, she would wait for the guy from Meals on Wheels to bring her another bag of ham salad or egg salad sandwiches.

It was like this for about four years.

She didn't complain much, except about the tuna salad. She had a gallbladder problem and the onions in the tuna salad were hard on her gall bladder. She would try to pick the tiny shards of onion out of the tuna salad, but this got harder and harder as her eye sight gave out. (When she finally died, it was after a gall bladder operation. She survived the operation, but she had a stroke afterward that shut down her whole body. But that's another story.)

Anyway, when I would come to visit, she was always happy to see me because she could always talk me into cooking for her. I hate to cook and I hated to work around my mother. My mother learned discipline from the Nazi guards in the concentration camps. She expected you to follow orders and she expected you to do it right. There was no screwing up allowed around her. If you did, she would freeze you out, turn her sarcasm against you. Call you a baby or a fool. Tell you that you're a college professor and still you can't boil a stinking egg!

Like I said, I hated to work with and around her, but I cooked for her. She knew I was a fool with my hands, that I couldn't make the things she really wanted to eat like pierogi or golumpky, but she also knew that she could maybe talk me through some simple dishes. Navy Bean Soup was the one she had me make most often.

Like I said, I hated to work with and around her, but I cooked for her. She knew I was a fool with my hands, that I couldn't make the things she really wanted to eat like pierogi or golumpky, but she also knew that she could maybe talk me through some simple dishes. Navy Bean Soup was the one she had me make most often.We would start making the soup the night before by putting the beans in a pot full of a couple quarts of water. This would have to soak overnight. The first time she had me make it, I asked her why I just couldn’t follow the directions on the package, and let the beans soak under boiling water for a couple hours on the day we were going to make the soup. She just looked at me.

Then the next day, the day we were actually going to make the soup, we would start early in the morning, so that the soup would be ready for lunch.

I would chop up about four good sized onions. They had to be chopped really fine because of my mother’s gallbladder problem. As I would chop, she would watch from her wheel chair. Some times she would think a chunk was too big, and she would point it out. “There, that one!” she would say. “Are you trying to kill me?” And I would chop it some more with this old, skinny bladed knife of hers that she had been honing for 30 years, just a honed wire stuck in a dirty yellow plastic handle.

Then I’d fry up the onions in about 4 tablespoons of butter. I’d fry them until they were caramelized, just a sort of hot brown jelly with an oniony smell. This would take abut an hour. Meanwhile, I would be chopping up everything else, half a pound of carrots, two or three pounds of any kind of potato, 3-4 stalks of celery. It didn’t matter how I chopped those up. My mother’s stomach had no trouble with them. It was just the onions that were a problem. So I chopped everything else pretty rough. I like big chunks of stuff in my soup.

I would take these chopped vegetables and add them to the frying onions and cook and stir all of that for about ten minutes on a low flame. Next, I would add the beans and the water they were in, along with too much pepper and salt. At this point my mother would stop watching me. She would figure that there’s no kind of damage I could do to the soup, so she would wheel her wheelchair out of that tight little kitchen and into the living room where she would turn on the TV, The Oprah Winfrey Show or the Noon News or anything else except soap operas. She hated soap operas, all that talk and people who were worried about stupid things.

I’d cook the soup for about an hour, maybe longer, and then I would carry a really large blue bowl of that hot navy bean soup to her and place it on her TV tray. She always said that she liked to eat like an American, on a TV tray So while I was finishing up in the kitchen, she would drag the TV tray up to her wheelchair, and she would ask me to put the soup right there.

I would and as soon as I did she would start crumbling saltine crackers into the soup. They were the final touch.

We would eat this soup just about twice every day I was visiting, lunch and dinner. If we ran out, I would make some more. It was better than the stuff my mom got from Meals on Wheels.

Wednesday, October 03, 2007

Poet Gabor Zsille Asks, What's Up?

I got a letter a few days ago from Gabor Zsille, a fine Hungarian poet and translator living in Budapest, and he asked me if there was something wrong. He hadn't heard from me in a long time.

I got a letter a few days ago from Gabor Zsille, a fine Hungarian poet and translator living in Budapest, and he asked me if there was something wrong. He hadn't heard from me in a long time. Three weeks ago I started doing a series of poetry readings across three states: Georgia, Kentucky, Illinois.

I drove approximately 1800 miles (3000 kilometers?). I read my poems about my parents, and I talked about their lives. It was a very good experience but that kind of travel is always harder than I want it to be. Sometimes I stayed with friends, sometimes I stayed in hotels. Always I was eating sweet heavy food that I shouldn't have been eating and drinking too much coffee and -- promise not to tell anyone -- even smoking a cigarette. Plus, I was seeing old friends who I've known for 30 years but haven't seen in 3 since I retired and moved down to south Georgia.

On top of all that I was not getting my usual exercise, no running or biking or walking or pilates or yoga. I gained 15 pounds over the summer while I was helping care for my wife's dying Uncle Charlie, and that weight sits heavy between me and the laptop on my knees.

On top of all of that I was reading poems aloud about my parents in front of groups large (300 people at the Women's and Gender Studies reading at Valdosta State University) and small (15 students in a class room on the fourth floor of Cherry Hall at Western Kentucky University), reading poems about all of that 20th century sadness, the kingdom of death, the slave labor camps, the concentrations camps, the sisters ripping their legs apart on broken glass as they fled the Germans, gypsy girls burning up like straw, all of that bad chemistry at the heart of the last century.

I got back home last Saturday night after a 14 hour, 800 mile drive. Since then I've been trying to get back to normal. I'm teaching an online creative writing class and had to catch up with all of students and their poetry projects. Teaching an online class gives both teachers and students a certain degree of freedom, but finally work has to be done, suggestions made, stanzas lengthened!

In addition, I have chores to do that you wouldn't believe. We live in a house that's 115 years old, and something is always falling down or falling apart and needing to be hammered back up! (I'm not going to tell you about my work on our swimming pool pumping system because you'll think I'm too middle-class, too bourgeois. Also, please don't mention the falling down part. We're trying to sell the house.)

And today, I volunteered to leave behind my students, my exercise, and my chores to drive with her to a meeting she has to attend in Macon, Georgia--home of Little Richard.

(Do you know Little Richard? He's the man. Here's a you tube of him singing "Tutti Frutti." http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ayNdjFyk1c Have you read his autobiography? It's amazing. A black gay man growing up in the middle of straight, disapproving Georgia in the 1940s and 1950s!)

My wife Linda’s an administrator at Valdosta State University in south Georgia, and she has to periodically attend these meetings. And when she does I like to drive her. She's a fine driver, but I just like to drive. In fact, she's a terrific driver. She taught me how to drive (and how to swim) the first year we were married. She said, "Honey, I don't want to be married to a man who can't swim and drive!"

So while she goes to her boring meetings that determine nothing (I didn't say that) but do give the administrators an excuse to get out of town and eat some bad food and probably smoke cigarettes and drink a little white wine over dinner, I wander around these cities, poking my long Polish nose into alleys and side streets, sniffing like a blind man for some historical spot that will bring all of that crazy Georgia past to me like some kind of Proustian madelaine.

And how are you, my friend Gabor?

The weather here is dreadful. 90 degrees in the day. Steamy. The sun nailed in the sky.

And the nights?

Don't ask.

john

PS: did you receive the books I sent?

Tuesday, September 25, 2007

God Drunk

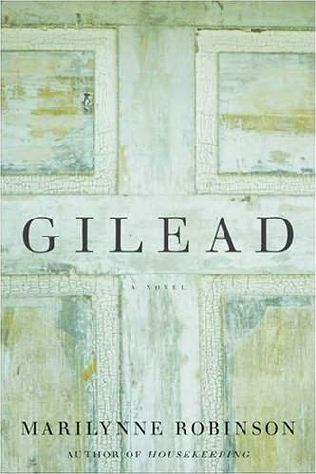

The novel Gilead by Marilynne Robinson is pretty great. (She also wrote one of my other favorite novels: Housekeeping.)

The novel Gilead by Marilynne Robinson is pretty great. (She also wrote one of my other favorite novels: Housekeeping.)I like the history and the prairieness and the popular culture references a lot, but I’m not sure what I make of the novel finally. It is so Christian, so God taken and God drunk. I figure that maybe Robinson is arguing that Christianity should return itself to the sort of humility it had at some point in the past when it was beset by existentialism. But I’m not sure if Christianity ever had that sort of humility. I know that the Catholicism I knew in the 50’s was never humble. It was pretty muscular. The Pope was a sort of ecclesiastical Uncle Sam rolling his sleeves back to punch the God-cursing Commie specter of Joe Stalin in the nose.

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

Update on "The Short View"

I’m getting a lot of comments about the blog I posted yesterday about Sept. 11. Some of them were sent into the comments space, and some have come directly to me. I’ve tried to encourage the folks who sent directly to me to post to the comment space, or let me post for them. I’ve succeeded in some cases, but not in others.

I’m getting a lot of comments about the blog I posted yesterday about Sept. 11. Some of them were sent into the comments space, and some have come directly to me. I’ve tried to encourage the folks who sent directly to me to post to the comment space, or let me post for them. I’ve succeeded in some cases, but not in others.The comments have generally been of two kinds. There are the people who wrote in and said they too were thinking about where they were and what their friends were doing that day in 2001. Some of them wrote about the friends they had lost. These are the people who, I guess, felt the way I did yesterday.

For me, it was a day of mourning and remembering the trauma that ripped through my family. My wife Linda’s from Brooklyn, and she has a lot of relatives in the New York area. We were both thinking about them yesterday, and thinking too about their friends and their friends’ friends, all that wide and complex set of connections we all worried about on 9/11 and the weeks after.

Like I said, it was a day of mourning for me, and I think it was a day of mourning too for some of the people who wrote in and told about their friends and family.

The other letters I got were from the people who felt that this anniversary of 9/11 called for something more than mourning. These letters suggested that the kind of emotions I was talking about in my piece “The Short View” were the kind of emotions that have gotten us into trouble politically, militarily, socially, and culturally. These letters suggested that politicians use the kind of emotions I was showing to their own ends, and that in this case, the ends were terrible, the continuation of a war in which there are more and more deaths each day with little accomplished and less in sight.

I really can’t argue with that bleak assessment of the war. The deaths are in fact terrible. I haven’t done much research but I’ve done some, and the numbers of dead and wounded suggest that there are a lot of people here and in Iraq who are mourning.

As of today, the Iraqi military and civilian death count since 2005 when the Iraqi Coalition Casaulties site (http://icasualties.org/oif/default.aspx) started counting is about 43,000. That’s about 37,000 Iraqi civilians.

As of September 10, 2007, the site reports 3,765 confirmed US military deaths with 9 pending confirmation. The Department of Defense has confirmed a little less than 37,000 military people wounded or medically evacuated. The DoD also reports 122 US suicides.

I really don’t know how to begin thinking about all of the human cost in misery and pain. About 48,000 people dead and a country that’s been chopped up and blasted apart? I was talking to a mathematician yesterday, and she told me that a person generally can’t imagine more than a thousand of anything. 48,000 deaths of US and Coalition Forces and Iraqis? It’s difficult to imagine a number of dead people that high. And the number of wounded on both sides? And the number of people touched by those deaths and those wounds? That’s harder still to imagine.

How high is it? It’s hard to say, but I know I’ve had students who went to Iraq, fought and were wounded in Iraq. We all know people “on our side” touched by this war. I used to commute a lot when I was teaching in Illinois and living in Georgia. Every week, I would pass through the airport in Atlanta – it was full of soldiers going to Iraqi. The odds are that some of those boys and girls never saw the US again. And the numbers on the other side? Higher still. Higher still.

When I wrote the “Short View” piece in 2001, I was responding to that time and what was going on in America. Am I ready to give up the “Short View” and start thinking only about the “Long View”?

I don’t think so.

I’m not an either/or sort of person. I can’t say I’ll stop being emotional, taking the short view, and start being rational and take the long view. I tend to see things as both/and. I don’t know where that comes from, maybe from my parents who both went through the slave labor camps and came out two very different people, maybe it comes from growing up bi-lingual and bi-cultural and generally confused by how complicated the world is. Whatever the reason, I’m hesitant to pin myself down, choose one side or the other.

I can take the short view, feel grief and mourning, but I can also feel that we need to close the book on America and Iraq, just the way the British did in 1917 when they invaded the country and found themselves fighting a war they could never win, against a country that didn’t want to see anything of them except their backside.

Tuesday, September 11, 2007

The Short View and the 9/11 Terrorist Attacks

I wish I could take the long view the way you do, Bill: look at the attack, and see it the way it probably is: Bush seeing this as his way of putting a lock on his second term, Americans showing their true nature by making money on increased gas prices, Hollywood being angry because this will put the next Bruce Willis film on hold for 2 weeks. The long view: we're all self-serving crooks.

I'm not good at the long view. I'm more of a short view guy: One of my wife Linda's cousins saw the first tower go down from her office. Her name is Lisa. She was a wonderfully fat baby. One time her mom, Linda's Aunt Anne, dressed her in a tutu, and Linda's dad Tony laughed and laughed, and still 25 years later the family talks about the tutu and how much we all loved her in her tutu and laughed with joy at her beauty.

Lisa got out okay. She was evacuated, and finally found herself across the river at a phone booth in Hoboken, New Jersey. She called home to Aunt Anne and Uncle Buddy. He’s also a short view guy: He was with Patton's soldiers when they freed the first concentration camps. He still shakes and cries when he remembers the piles of corpses.

My niece is an emergency room nurse at NYU hospital (I think I saw her in the background on an NBC spot about the hospital--but I wasn't sure. She looked old and tired and gray with pain). Her dad, Linda's brother Bruce, was calling her and calling her to make sure she was okay. Finally she got through to him late in the afternoon on Tuesday. He begged her to leave the hospital, said he would drive down from Connecticut and get her. Cried and begged her. He said he was her father and she had to listen to him. (Bruce isn't much of a crier. He's a jokey, tough Brooklyn guy.) But she was his baby and he wanted her away from all of it. And she said she couldn't leave. He cried some more and pleaded, and she hung up on him. She had to get back to work.

And all those people looking for their relatives and friends, holding pictures up to the TV cameras and telling us about how some guy was a great friend, and he was a waiter in a restaurant at the top of the building. And I see this picture of this poor foreign looking schmuck with a big nose and a dopey NY baseball cap that's way too big, who probably came here with a paper suitcase and thought that working up at that restaurant was the greatest thing possible in the world. And the friend hoping to find this guy thinks this guy is alive someplace, maybe in a coma in some hospital.

And I know there's not a chance in hell this guy or any other guy or gal in any of these pictures is alive. They're dead, all dead, but I wouldn't tell this guy holding the picture.

Boy, these are stories that touch me so hard I can't think about the other stuff, the long view.

Saturday, September 01, 2007

Upcoming Poetry Readings

The first reading is for the lecture series sponsored by the Women's and Gender Studies program at VSU. It will be at 7pm, Tuesday, Sept. 11 at the Bailey Science Center at Valdosta State University.

Here's some info about that and the entire series:

http://www.valdosta.edu/womenstudies/UpcomingEvents_000.shtml

The following week I'll be giving a reading at Western Kentucky University, at 7pm, Tuesday, Sept. 18.

The next day, I'll be reading my poems about my parents as part of the Eastern Illinois University conference on World War II and James Jones. The reading is at 3pm, Sept. 19, in the library.

Here's the website with further information:

http://evff.net/conference-schedule-tentative/

All of the above are free and open to the public, but if you can't come, you can hear and see me read on line. Janusz Zalewski and Henryk Gajewski put together a website of readings from the January 2007 PAHA conference.

Here's that link: http://gajewski.tv/poets/

Friday, August 24, 2007

Wednesday, August 22, 2007

Uncle Charlie, August 22

But Uncle Charlie is coming close.

Earlier, he was upset because he wasn't dead, and I think that was keeping him alive, contributing to his agitation and keeping him with us.

He really thought he was a goner at first. The doctors operated on him, looked at his pancreas and said, 3 weeks tops. One guy gave him a week. That was in mid May, and Charlie is still with us. But he just wants it to be over with. He didn't want chemo or radiation. He just wanted it to be over.

When the hospice started, he thought he would be dead in a week or so. The hospice nurses came to his house for the first few days and gave him hospice care there. This was hard for him because he was in a lot of pain and getting a lot of pain killers. When he asked to go to the actual hospice unit, he thought he would be dead in a day or two.

Then the dying just went on and on, and he just wanted to die. When he was awake and clear, he'd ask repeatedly if he could go home. He was sure that the hospice care was keeping him alive, and he didn't want to be alive any longer. That was Monday, the day I left Hollywood, Florida, and drove back up to Valdosta.

I talked to his brother Tony today, and he finally got someone to talk to him at the hospice. A nurse told him that she thought Charlie had another couple of days. Charlie's terminal agitation has stopped. He stopped talking too, even the raving that he was doing. He's lying tucked under a sheet--breathing hard, really hard, staggered, drawn breaths.

But life is hard to give up on.

When my mother was dying, she couldn't talk, couldn’t eat, couldn't move any part of her body. All she could do was blink her eyes, and I asked her if she wanted to die or if she wanted me to try to keep her alive. I told her to blink if she wanted to stay alive. She blinked.

Tuesday, August 21, 2007

Mike Rychlewski Talks about Dying

Here’s what he sent me about some of the people he loved who died:

Dying from burns over 70% of his body, my father flopped and flailed like someone getting shock treatment or being blasted in the chest with electric mittens. Two nurses were holding him down as he popped up and down.

My mom was lying on her bed in the nursing home with her back to the dark TV screen in the middle of the afternoon when there was a Cub game on. I asked her why she wasn't watching it--she had never missed a game--she said she wasn't interested.

My uncle got up from his bed at the nursing home, walked out the door, hailed a cab and took it ten miles across Denver. The found him that night wandering around the neighborhood he grew up in as a boy.

My other uncle sat on the edge of the hospice bed and took out an imaginary pack of cigarettes from his breast pocket, shook one out, reached into his front pocket for imaginary matches, pealed back the cover, lit the match, held it to the cigarette, took several puffs, finally got it going, and sat there for ten minutes smoking it. It was a performance that would have put Marcel Marceau to shame.

My bachelor cousin at 93 was lying in his gentleman's nursing home hospice room and his nephew from Virginia, who had been bearing witness for two months, finally had to go back to his wife. He said, "I’m leaving now, Mac." Mac said, "Wait!" and he summoned the nurses, insisted they dress him--he was the most elegant dresser I ever knew--he got on his white shirt, blue sport coat, gray slacks, silk tie, lapel handkerchief, spit-shine shoes, took off the oxygen and the IVs, slowly walked to the dining area and ordered the two of them tea and cake. They sat there and ate it. Mac said, "This is what I want your last memory of me to be."

.

There's no meaning, no purpose, no hidden agenda.

.

No one's death is more or less dramatic or poignant.

.

There is no scheme to the universe and we're neither less nor more than nothing.

.

The love of the people we know.

.

Period.

.

If you don't have it, God have mercy on your soul.

[The photo above is of Mike at the graves of his Mother and Father, St. Adalbert's Cemetery, Niles, Illinois, Summer 2005. My parents are buried here also.]

Saturday, August 18, 2007

Hospice, August 17

But there didn’t seem much chance of that. Lying in his bed, he seemed quieter, the terminal agitation and restlessness had stopped. Charlie looked at his brother Tony and didn’t move—it was like Charlie was surprised we were there and didn’t have the words or energy to tell us what was going on.

After a minute, he said, "I had a strange experience today." And he tried to tell us about a dream that he had, but he wanted us to know that it wasn’t a dream but that it had really happened, and he wanted us to say that we believed him when he said it really happened. And I said I believed him, and I told Tony who couldn’t hear very well to say that he believed, and he looked at me with a question and then he said he believed.

The story Charlie told was confusing. It must have been some kind of half dream half waking reality that he experienced, and what made it hard for me to understand his story was that I could hear some of what he said but not other parts.

The story was about his home, and somebody trying to take his home away from him, and this person was a communist and a guitar player, and she tried to get the house from him for $99 but he fought her off. He wouldn’t sell no matter what terrible things she did to him, and he kept talking about the way she tried to get him to sell, offering more money and less money and then more money again. And during all of this pressure to sell, Charlie saw above and behind her head these messages that appeared in different colors, yellow and blue and red, and I asked him what the messages meant. He couldn’t tell us because he couldn’t read the messages but he knew that he wouldn’t sell the house for $99 or $77 no matter what she said or what terrible things she did.

And then he stopped talking and asked if I understood. I said I did. I had read in one of those hospice pamphlets that they have lying around here that you should agree with whatever the dying say, so I said I did. And the pamphlet must be right because he seemed happy that I understood. And really, I think I did understand.

Charlie then said, "Give me a hand," and I thought, Oh oh, he’s going to try to get out of bed and that’s just what he started doing -- his feet started moving to the edge of the bed and he gripped the bed rail and started pulling himself up. And I thought, the terminal agitation’s back.

Tony called the nurse, and she came in, and I thought she would try to put Charlie push back into the bed but she didn’t. She helped him out of the bed; she helped him get his feet in his red socks on the floor – and when she had him standing, she held his arms while he took a step and then another toward the bathroom. It was a miracle.

I had to get out of the room – it was too much, and I went into the lobby and sat down. Five minutes later, Tony wheeled his brother out of the room in a wheel chair. They took a spin around the room and went into the dining area and Charlie sat looking out the window toward Pembroke Ave and the north side of Fort Lauderdale.

The gigantic white and blue clouds lifted off the horizon and rose to the rich blue at the top of the sky. It was the kind of day that probably set kids dreaming about visiting Tahiti or Fuji or the islands Herman Melville visited as a boy when the 19th century was still a kid and people traveled across oceans on sailing ships that were like clouds anchored to clean-planed oak planks.

After a while he said he was tired, and Tony wheeled him back into his room, and he and I helped Charlie get out of the chair and into the bed.

As soon as he laid his head down on the white pillow he fell asleep.

Thursday, August 16, 2007

Terminal Agitation, The Hospice, August 14

But the nurse said she wasn’t joking and after Linda got off the phone with her, we googled "terminal agitation" and there it was, on a page dealing with hospices.

Here’s what we read:

What is Terminal Restlessness or Agitation?

Those who work with the dying know this type of restlessness or agitation almost immediately. However, the public and patient's family may have no idea what is going on and often become quite alarmed at their loved one's condition. What does it look like? Although it varies somewhat in each patient, there are common themes that are seen over and over again.

Patients may be too weak to walk or stand, but they insist on getting up from the bed to the chair, or from the chair back to the bed. Whatever position they are in, they complain they are not comfortable and demand to change positions, even if pain is well managed. They may yell out using uncharacteristic language, sometimes angrily accusing others around them. They appear extremely agitated and may not be objective about their own condition. They may be hallucinating, having psychotic episodes and be totally "out of control." At these times, the patient's safety is seriously threatened.

Some patients may demand to go to the hospital emergency room, even though there is nothing that can be done for them there. Some patients may insist that the police be called ... that someone unseen is trying to harm them. Some patients may not recognize those around them, confusing them with other people. They may act as if they were living in the past, confronting an old enemy.

I got that from the Hospice Patients Alliance. Here’s there link:

http://www.hospicepatients.org/terminal-agitation.html

But that didn’t come near describing what Charlie was going through.

He wanted so bad to get out of bed and stand up and walk out of the hospital that no word from Tony or the Nurses or the doctor could turn him aside. Charlie wanted to be on his feet and moving toward the door, and more than that. He wanted to walk out the door to the elevator and take the elevator downstairs and then walk into the parking lot and get into his candy-apple red 98 Mercury Sable and drive away from this hospice like a man being chased by the devil.

But he wasn’t going anywhere, even though he moved his feet toward the foot of the bed and he tried to grab the bed rails with his hands and pull himself up. He tried that over and over. You’d put his feet under the sheets, and he would try to lift his shoulders up off the bed. You’d tell him that he couldn’t lift himself up, and he’d try moving his feet toward the edge of the bed. And all the while he’d be talking about leaving the bed and getting stronger and walking out of the hospital. He’s spent days trying to get out of bed and telling us he was feeling fine and was ready to go home—even though he was down to 80 pounds and his skin and eyes were a sandy yellow color.

And when he wasn’t talking about how good he felt, he talked about people he had to call and things he needed to do, the projects he was working on and the places he needed to shop at. His mind was working overtime at time-a-half spinning through all of the unfinished business of his life. He was like a man on fire.

Thursday, August 09, 2007

News from the Hospice

Charlie thought his death was imminent and so he decided he would go to a hospice. The hospice is pretty rough: dirty windows, small rooms, two patients in a room, overworked nursing staff that complain about patients being too demanding. The nurses don't seem to be aware that the patients are dying and have a right to be demanding. I heard one nurse say to a dying man, "You've pressed that button 7 times, there's nothing I can do for you. I have other patients to take care."

It's called "The Hospice by the Sea," and when I first heard Charlie was going there I had this image of a place near a beach where you could look out a window and see waves under a rising sun, and trees and gardens. But it's not that way. The place is in the middle of Hollywood, Florida, a heavily urban city just north of Miami. You can't see the sea. There are some pictures though of water.

Anyway, Charlie is there waiting to die, and it's not happening as fast as he thought it would. In fact, he perked up as soon as he got there. He started complaining about the room, the nurses. He's in some pain too. They only give medication on demand for some reason, and Charlie has always been shy about making demands. He went 8 hours yesterday without anything.

He thinks that the stronger the pain gets the closer he is to death. He's afraid that the morphine is forestalling death. We got him to agree to take something for the pain finally when it got impossible.

While Tony and I work on the condo and Charlie's stuff, Linda is there from 9 am to 8 pm each day. Keeping an eye on Charlie and arguing with the nurses.

Yesterday, we were sitting there and the guy next door got so annoyed that he couldn't get a nurse's attention that he knocked his chair over, and started banging it against the wall.

Finally, a nurse came. I don't know what this guy's story is, but he's from Peru, he's dying in Hollywood, Florida, and his wife is in Peru and doesn't know where he is. He wants to call her up but the nurses just hand him the phone and he can't figure out how to make an international call.

At one point his wife called. The nurses put her through to his room, but he couldn't handle the phone and lost the call.

Linda and I are furious with this place.

But Charlie is adamant about remaining: "I'm staying here until I die."

Sunday, August 05, 2007

Let's Have a Party

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

A Conversation with John Guzlowski

Last January, I went up to Atlanta and met Bruce Guernsey in a Ruby Tuesday Restaurant to do the following interview for Spoon River Poetry Review.

Last January, I went up to Atlanta and met Bruce Guernsey in a Ruby Tuesday Restaurant to do the following interview for Spoon River Poetry Review. .

THE INTERVIEW:

JG: Yeah, I was reading a lot of Hawkes and Pynchon at the time, but I haven’t been reading much contemporary fiction for years. I’ve been writing poems for a long time, though, but not so many as recently.

SRPR: What do you think has gotten you going? Really, it’s incredible the number of poems you’ve written lately. And they’re hardly postmodern.

JG: I think one of the things that has me writing as much as I am was the death of my father and my mother’s increasing bad health and then her death. I’ve just been thinking about the two of them more, and a lot of the poems come out of my parents’ experiences. I think this is what’s fueling all of the writing.

SRPR: “Death is the mother of beauty.” Yeah, there’s no doubt of it: there’s this organic process involved in the writing of poems that has to do with working through some painful experience. It’s clear that something deep inside has sparked you here.

JG: One thing that happened is that after my father’s death, my mother started telling me stories about her time in Germany. She had never told me these before, so that hearing all of her stories gave me a sense not only of her experiences but of my father’s as well. Many of the things she told me about had really happened to my father. I think that hearing her stories and then putting them next to my father’s got me thinking about the two of them. So, a large part of my writing lately has come from finding a comparable experience my father had to what my mother had told me about her own life—things she never told me before, by the way. She was the kind of a person who would not talk about her experiences, and, honestly, sometimes there were things you just didn’t want to hear.

SRPR: Well, I must say they are not among the happiest I’ve ever read.

JG: In one of the last conversations I had with her before she died, we talked about when she and my father met. I had written a poem about why my mother stayed with my father because I had always wondered why she had. It was a relationship that seemed to be so antagonistic and so bad for the two of them. Maybe that’s why I wrote a poem about it. Afterwards, I asked her if she had ever been happy with my father, and I thought maybe she would tell me about some kind of courtship experience they had had, maybe what it was like in Germany right after the war. Even though it was spring back then and everything was in bloom, she started telling me a story about my father and her that was so ugly, I said “Mom, I don’t want to hear this.” I was hoping for something romantic, but with that story, I didn’t want to hear any more. That was really the last time we spoke about their experiences in Germany.

SRPR: There does seem to be a kind of implied dialogue in your poems as you go back and forth with titles like “What My Mother Told Me” or “What My Father Said” about this or that. I get the feeling of your being almost a little kid in a way, going from one parent to the other trying to get at what was the truth.

JG: Yeah, yeah. I feel that very strongly. I had a poem just published online called “Why My Mother Stayed with My Father,” and I sent the link to a friend of mine. She wrote back and wanted to know how much of the poem was true, and I said to her that it was all true but was a “child’s” truth. That’s the way I saw their relationship whether what I saw was actual or not. It was true to a child’s eyes, mine, as it appeared to me.

SRPR: You still are a child, John.

JG: No, really. I kept waiting for someone to contact me and want to publish a book of my poems. I waited and waited and waited, and what finally was the spur to putting the chapbook together was that I was going to give a reading at a World War II conference, and I was going to have a session all to myself. I thought it would be nice to have something to pass out to the people there, so I gathered together enough of the poems to make twenty-eight pages and put together a cover and went to Copy-X and ran off a hundred copies.

It really was a transforming sort of experience because I never thought that I would get the kind of response to these poems that I got. The first printing cost me about $132 for the hundred copies. My friend and colleague John Kilgore helped me set it up on a word processing program because I was pretty ignorant about what I was doing. I sold all those and ran off more copies over the years. About eight hundred copies altogether. It’s really brought me a long distance.

Bohdan Zadura, an excellent Polish poet living in Poland, saw a copy and asked to translate the poems into Polish, and then Czesław Miłosz saw a copy later and did a review of it that’s included in his last collection of essays. Then later I took a bunch of the poems and submitted them to the Illinois Arts Council and won a fellowship for 7,000 bucks.

SRPR: That’s a great story. Really.

JG: It’s been amazing. Who would have thought? So when people say to me that they’re thinking about self-publishing, I say “Go! Self-publish, by all means!” I was on a panel a while back about this very topic. There were four of us, and the other three all said the same thing: you need to be evaluated by your peers and if you print the book yourself, there’s no peer evaluation, and on and on they went. I said, instead, I printed this little book and it was a good

thing to do. It was the right thing to do.

JG: Contests! I think of all the money I’ve spent sending my book around for $25 a pop to twenty or so different contests. I could have published the book myself for that money. Published and distributed it.

JG: I speak Polish, or a little anyway. What I call “kitchen” Polish — I speak it and have tried writing in it. In fact, one of the first poems that I wrote about my parents, “Dreams of Warsaw,” I wrote an early version in Polish and then read it to my parents. My mother said, “It sounds like a country and western song.” That’s because even though I thought it was in free verse, there are just so many rhymes in Polish that the poem came out with a kind of rhythm to it and so sing-songy that my mother said it reminded her of “a hillbilly tune.”

SRPR: What did you do then—did you translate it into English?

SRPR: Could you write the poem out for us in Polish?

SRPR: I think I’m trying to get at a point here. Your poems are wonderfully simple and direct and remind me in that way of some other poets who are essentially writing in English as their second language. Charles Simic is an obvious example—from Yugoslavia to Chicago—and then another Illinois poet, Carl Sandburg, who grew up hearing Swedish before he knew English. And then there’s John Guzlowski, who also moved to Chicago, writing in a similar uncomplicated style.

JG: It’s funny you say this because I have a PhD in English and have taught for what, almost thirty years, and still get idioms mixed up and words turned around. I know there were times when the students thought for sure that I didn’t know the language. You know, my mother learned to speak English very quickly, but as both my parents got older, they lost a lot of what they’d learned.

SRPR: I guess that’s because they learned it. Polish they lived. That’s like this guy I knew in college who grew up speaking Spanish but was absolutely fluent in English. No accent or anything until he’d get really upset about something, and then he reverted to Spanish. His emotional life was connected to those first sounds he heard, but I guess that’s where our emotional lives are, down in those deep recesses of language.

JG: That was sure true for my mother especially, who knew all kinds of Polish folk sayings and songs. Real simple, direct bits of wisdom. I think about what I was paying most attention to when I was in my teens and that was folk music. Maybe I was attracted to it because of that same simplicity.

SRPR: Elemental, that’s how I’d describe your poems. Hardly ornamental, thank God. But now that I’ve been praising the hell out of you, do you think you sometimes get a little repetitious?

JG: Oh yeah. I worry about that. But I think finally what I’m doing is trying to get deeper into a poem, to elaborate on something I did in an earlier poem.

JG: The new book actually had all the poems in it at one time. But it was about 180 pages long. I knew that wouldn’t work. So I tried to develop a strong sense of narrative as a way of unifying it, which is ironic in a way because the book starts out backwards with the death of my parents and moves all the way back to their childhood in Poland.

JG: Yeah, I did a lot of short stories, but when I started writing poetry, I stopped writing fiction. It’s been twenty-eight years since I’ve written any fiction, though my own complaint about my poems is that I sometimes think they’re too prosy. Just too many "that’s" and "which’s" in the poems. Too much reliance on transitional words that we use to make sentences

SRPR: Thank you for saying that. I don’t mean about your work, I mean about so much I read that’s prose chopped at various predictable places. Why bother with line breaks?

JG: Well, I try to work on those. Probably the poet who has influenced me the most is Robert Frost. I’m always thinking about the way he broke his lines, especially in the great narrative poems like “Mending Wall” and “Home Burial.” That’s poetry.

Bruce, can I say one last thing? About Spoon River?

SRPR: Sure. Go ahead.

JG: I’d like to thank you for reconnecting me with the journal. It represents a lot to me. One of my first poems about my parents appeared in Spoon River back when it was a quarterly. The poem was “Pigeons,” and Lucia Getsi was kind enough to print it. In a slightly different form. As I recall, she felt the opening moved too slowly, and she took the time to ask me to rethink it and she even gave me some suggestions. What I’ve come to realize over the years is that not many editors would do that. I rewrote the poem, and she took it. I was very happy to see it in Spoon River.

The journal also means a lot to me because it reminds me of all the fine poets and writers who have come out of central Illinois in the last decades, you and Lucia and Curt White and Jim

McGowan and Kathryn Kerr and Helen Degen Cohen and Kevin Stein and Ray Bial and David Radavich, and so many others whose names I’m forgetting but whose writing moved me. Really, it was an amazing gathering, and I hope Spoon River is here for decades and decades more to give poets a place to connect with readers and other poets.

SRPR: That’s kind of you, John. We plan to keep it going, one decade at a time.

Monday, July 16, 2007

I'm No Sharon Olds.

As I was checking out Ager’s blog, I noticed a letter from Sharon Olds. Deborah had found it somewhere and reprinted it at her blog. Sharon is a substantial poet and she had been invited by Mrs. Bush (wife of the Decider) to attend a Library of Congress poetry event and to have breakfast afterward at the White House.

Sharon’s letter was addressed to Mrs. Bush and explained why, although Sharon really believed in the good that events like the one at the Library of Congress could do, she wouldn’t attend because of her opposition to the undeclared and devastating war President Bush and America were waging against Iraq.

I read Olds’ letter, agreed with her completely about the war, and wrote a comment that I left at Deborah Ager’s blog.

Here’s what I wrote:

Hi, I just sent in an application to read a couple of my poems about my parents and love at the Valentine’s Day “poetry at noon” session at the Library of Congress.

(One of the poems is Why My Mother Stayed with My Father and the other is What the War Taught my Mother. My parents met in a concentration camp. It was never Romeo and Juliet for them. I figure I’ve got a chance as a novelty act! Not your traditional love poem!)

Anyway, I’m a long shot at best (the 500,000 poets in America who are better than I am would have to decline their invitations to read at the LC before I got a chance), but reading your post of Sharon Olds’ letter makes me think about what I’d if I were chosen.

Would I go?

I hate to admit this because it makes me seem petty and non-serious and a traitor to so many things I believe in, but yes, I would go. Absolutely.

The chance of me getting invited twice to the Library of Congress is about the same as the odds of me giving birth to the next Mother Theresa (I’m male and no longer Catholic and not even very charitable–lepers stay away from my door!). If I were invited, it would be a one time invitation.

Sharon Olds? She can turn down Bush and still have a chance of being invited by Obama or Hillary or John Edwards. Probably even a better chance. For weekly cabinet meetings maybe. Or brunch or something.

But me?

It wouldn’t matter if Barack or Hillary or John were in office. It wouldn’t even matter if my brother or sister in law were in office. I wouldn’t be invited.

So, I’m telling everybody now (and I hope they hear this at the White House and the Library of Congress!!) that if invited I will attend, and I will pay for my own carfare (from Valdosta, GA) and my own lunch!

John Guzlowski–poet-in-waiting

As I was checking out Ager’s blog, I noticed a letter from Sharon Olds. Deborah had found it somewhere and reprinted it at her blog. Sharon is a substantial poet and she had been invited by Mrs. Bush (wife of the Decider) to attend a Library of Congress poetry event and to have breakfast afterward at the White House.

Sharon’s letter was addressed to Mrs. Bush and explained why, although Sharon really believed in the good that events like the one at the Library of Congress could do, she wouldn’t attend because of her opposition to the undeclared and devastating war President Bush and America were waging against Iraq.

I read Olds’ letter, agreed with her completely about the war, and wrote a comment that I left at Deborah Ager’s blog.

Here’s what I wrote:

Hi, I just sent in an application to read a couple of my poems about my parents and love at the Valentine’s Day “poetry at noon” session at the Library of Congress.

(One of the poems is Why My Mother Stayed with My Father and the other is What the War Taught my Mother. My parents met in a concentration camp. It was never Romeo and Juliet for them. I figure I’ve got a chance as a novelty act! Not your traditional love poem!)

Anyway, I’m a long shot at best (the 500,000 poets in America who are better than I am would have to decline their invitations to read at the LC before I got a chance), but reading your post of Sharon Olds’ letter makes me think about what I’d if I were chosen.

Would I go?

I hate to admit this because it makes me seem petty and non-serious and a traitor to so many things I believe in, but yes, I would go. Absolutely.

The chance of me getting invited twice to the Library of Congress is about the same as the odds of me giving birth to the next Mother Theresa (I’m male and no longer Catholic and not even very charitable–lepers stay away from my door!). If I were invited, it would be a one time invitation.

Sharon Olds? She can turn down Bush and still have a chance of being invited by Obama or Hillary or John Edwards. Probably even a better chance. For weekly cabinet meetings maybe. Or brunch or something.

But me?

It wouldn’t matter if Barack or Hillary or John were in office. It wouldn’t even matter if my brother or sister in law were in office. I wouldn’t be invited.

So, I’m telling everybody now (and I hope they hear this at the White House and the Library of Congress!!) that if invited I will attend, and I will pay for my own carfare (from Valdosta, GA) and my own lunch!

John Guzlowski–poet-in-waiting

Sunday, July 01, 2007

FAMOUS FOR BLOGGING!

I said sure and kept writing about the swamp and the smoking and sending the posts to Charles Fishman.

That led to his asking me to write an article about how I got started blogging and what the point of it was and what writing a blog was like. I wrote the piece.

The piece appears at New Works Review, along with the entire epic of the Smoking Swamps that smogged up Valdosta, Georgia, for more than a month.

Here are the links:

Smoking Swamps--http://new-works.org/9_3guzlowski/swamps.htm

Blogging essay--http://new-works.org/

Wednesday, June 27, 2007

Brushes with Fame

(I'm thinking that maybe not many people remember Tom Ewell. That's what fame is like.

Wednesday, June 20, 2007

59th Birthday Post!

Hi, I wanted to post something special for my birthday, but now that I'm going to be 59 I've starting to get lazier so I'm just going to re-cycle something I wrote when I was 54. Hope you don't mind.

Hi, I wanted to post something special for my birthday, but now that I'm going to be 59 I've starting to get lazier so I'm just going to re-cycle something I wrote when I was 54. Hope you don't mind.I'm 54 and next year will be 55

our northern walls. The next year

Wednesday, June 13, 2007

Players in the Dream, Dreamers in the Play

I read Marian Shapiro’s book of poems Players in the Dream, Dreamers in the Play on the plane flying to and from Detroit last weekend for a Polish American Historical Association meeting; and I enjoyed those poems very much.

I read Marian Shapiro’s book of poems Players in the Dream, Dreamers in the Play on the plane flying to and from Detroit last weekend for a Polish American Historical Association meeting; and I enjoyed those poems very much.Usually, for me, flying isn’t the best way to spend my time. I commuted by plane from Valdosta, Georgia, to Central Illinois every week for two years, and doing that kind of traveling will sour you pretty much on being in close quarters with extremely strange strangers. But don’t get me wrong, I would have taken to Marian Shapiro’s poems even if I wasn’t flying.

The voice in her poems is a calm, smart, affirmative voice. It reminds me of one of my favorite poets, Elizabeth Bishop. Bishop can take the most harrowing sort of experience and see it plainly and lovingly.

I felt this throughout Marian’s book, but maybe I felt it most in her poem “Inside Looking Out”; two worlds come together suddenly in that poem, and one of the worlds is scary and threatening, but Marian’s voice and the surprise in it makes that world a puzzle and a mystery to be examined and wondered over.

Marian’s not frightened or shaken in her poems, just amazed and wondering. It's the way kids are when they meet "the strange." They want to look and consider; they want to play with the mystery and the strange things they find in it. If you’ve ever seen children looking at a chicken and wondering about it, you will know exactly what I mean.

That's the image I get most fully and most often from Marian’s fine poems, the image of someone playing with the things we don't understand or the things we fear. I don't mean “playing” in any kind of goofy way, but rather in a serious way, the way children and the best artists play with the strange gifts the world offers them.

I see this in so many of Marian’s poems, in the things she writes about and the ways she writes about them. These are poems to read over and over again, whenever we need to remind ourselves that the world's troubles and mysteries are maybe best viewed with calm and wonder and love.

Here’s Marian’s “Inside Looking Out” poem, the one I mentioned above:

Inside Looking Out

Through the slatted shutter, or

the fluttering of a pale peach curtain, I

glimpse a small white dog (poodle? terrier?) leaping,

light with freedom. The owner stands by, benignly.

Lovely day. Summer sun reflected in

puddles of last night’s shower. Laughing girls

as background music. Truck horns on an unseen

highway. Doppler of a distant freight

train. Mozart from an open window.

Who would have thought it! Sudden as

a nightmare, springing from the nowhere

of once and when, black mouth gaping, a wild

mangy creature (wolf? coyote?) wraps teeth

around dog collar as you or I might deftly

loop crochet hook into wool. Blood, cotton balls

of fur, guts, bones in slivers, shrieks and barks,

howls and the soft sound of children weeping. Is

this my dog? Was this my dog?

If you're interested in seeing more of her poems, you can click on the Amazon link to her book Players in the Dream, Dreamers in the Play. You'll find the link by scrolling down and looking on the right of the screen.

Sunday, June 03, 2007

Tony Calendrillo's Art

I've known Tony for about 35 years now. He's an artist and my father-in-law. When I first met him, he wasn't doing much painting. He was 50 and busy with his day job as a textile stylist in New York. He designed patterns on cloth, I believe. He'd draw soft yellow roses the size of a child's hand that would be used to decorate a white table cloth, or he'd work up a herring bone pattern in different shades of brown for men's suits. That kind of stuff.

He had some of his paintings on the walls of the house he and his wife Mabel shared in Brooklyn. They were good paintings. I remember one of him, a self-portrait. He could have titled it "Portrait of the Artist as a Young Brooklyn Guy Just Back from World War II." In the painting, he's holding a palette and some brushes, and he's looking at you like he's happy to be painting a picture rather than listening to Sergeant Novak's yap about doing latrine duty or holding the line against the Nazi tanks.

Tony seems happy and confident and eager in the painting, but you know he's serious too. The eyes in the picture give him away.

He wasn't painting much when I met him. I don't know if he was painting at all. He loved to talk about painting and art, and he loved to go to museums to look at paintings and drawings, but I don't think he was painting. It was like that was all behind him, left back in the past with the mustache the young guy just back from the war was wearing in that painting.

But then he retired.

And he started painting again, and doing water colors, and drawings, and doing art stuff he never thought about doing when he was doing art stuff. He started sculpting and taking art classes and displaying his paintings in galleries and hanging out with people who loved painting and drawing as much as he does. His paintings and drawings and watercolors were on exhibit in a one-man show at the Main Library in Bridgeport, CT, this spring. They may still be up!

Here are some of his paintings that I like a lot, and a photo of him working.

I don't know when Tony did the above painting of the building and the bridge. I asked Linda which bridge it was that's behind and above the house, and she said, "Maybe the Brooklyn bridge or the Manhattan bridge but you should call my father and ask him." So I called him and asked which bridge it was and where the house was, and he laughed and said, "I made it all up!"

Here's a photo of Tony working.

He's reading a book of Van Gogh's letters.